This month is the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education. This Supreme Court ruling ended the legal basis for segregation (separation based on race) in public schools. The Supreme Court itself was not clear about how quickly schools should act. In a second opinion in 1955, the court ruled that schools should act “with all deliberate speed.” The effort to fully integrate (bring people of different races together ) schools would be a long and serious struggle.

Dr. James Banks is a noted scholar and educator. When the Brown v. Board of Education decision was made, he was a Black seventh grade student in a rural Arkansas community. From his memories of the decision, he writes, “My most powerful memory of the Brown decision is that I have no memory of it being . . . mentioned by my parents, teachers, or preachers . . . It was completely invisible.”

Many Black communities met the ruling with silence for several reasons. The ruling brought a mix of hope and fear. Black communities were hopeful about receiving a fair education. However, they were afraid and uncertain about the future. White school board members controlled both Black and White schools. Many Black teachers worried they would lose their jobs. They also worried they would lose important cultural institutions. Black schools nurtured Black students and celebrated Black leaders. Many in the Black community also feared violence from White communities.

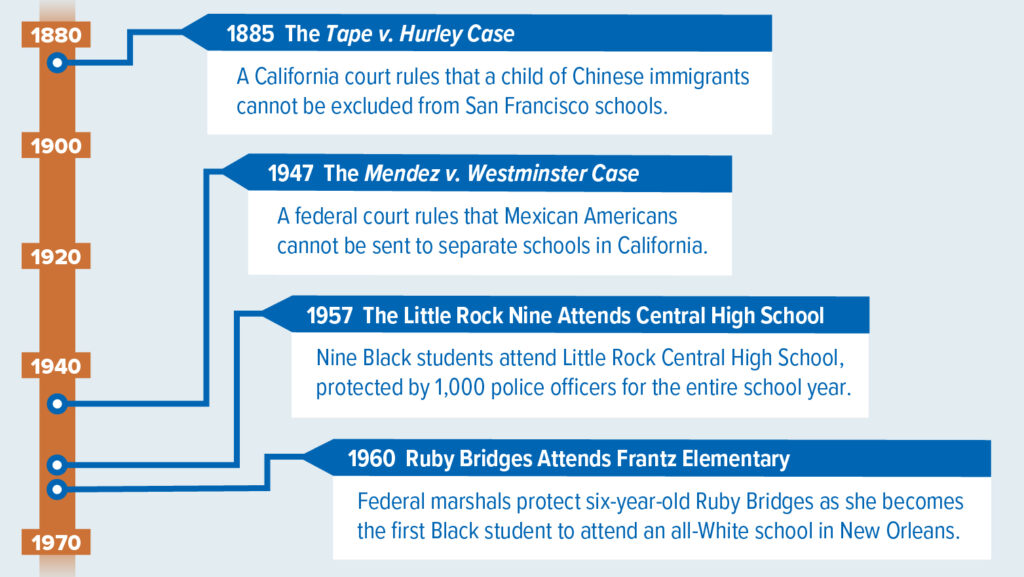

These fears came true. Many Black teachers and principals lost their jobs. Black students faced taunts, bullying, harassment, and threats. In 1957, three years after Brown v. Board of Education, nine students attempted to integrate Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas. Angry mobs threatened them. They blocked the students from entering school. President Dwight Eisenhower sent 1,000 members of the military to protect them. The military remained in Arkansas for an entire year.

In 1960, federal marshals protected Ruby Bridges. She was only six years old. She became the only Black child to attend William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans, Louisiana. A few miles away, more federal marshals protected Leona Tate, Gail Etienne, and Tessie Prevost. They attended McDonogh 19 Elementary School.

Resistance to integration took other forms as well. Arkansas governor Orval Faubus closed public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, after its first year of integration. In 1959, Prince Edward County Virginia also closed its schools. They gave White students money to attend private schools. No schools were available for Black students between 1959 and 1964. Only lengthy court battles would reopen schools in these and many other communities.

School integration has been a slow and painful process. Seventy years after Brown v. Board of Education, many communities are still having conversations about fairness and equal access to education.

What Do You Think? What does fairness and equality in schools mean to you?

Photo Credit: ASSOCIATED PRESS; TEXT: James A. Banks. “Remembering Brown: Silence, Loss, Rage, and Hope.” Multicultural Perspectives, 6(4), 6-8. 2004.